siteguide |

news |

touring |

emg |

history |

the works |

contact |

home |

Down And Out In New Grub Street

From October 1987 to August 1989, Donald was a contributor to Premiere Magazine's "MovieMusic" column.

These pieces (with a few tasty revisions) will be featured in this section. The following appeared in the December '88 issue.

Tell Blondie To Break Out The Ice

by Donald Fagen

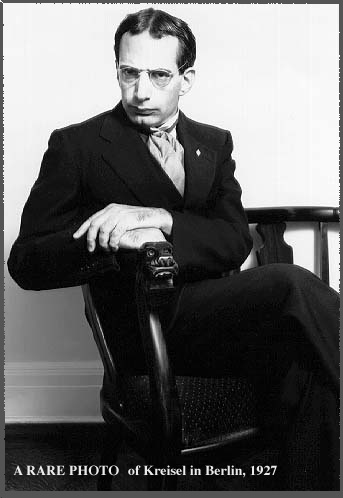

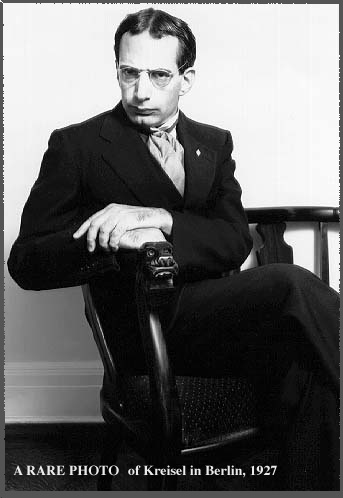

VIRTUOSO, AVANT-GARDIST, TUNESMITH, FILM COMPOSER, television personality: Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisel (1899-1988) played each of these roles gracefully during his long, productive life. Driven from his native Germany in 1933 by the gathering eddies of war, this slight, bespectacled member of the Weimar intelligentia came to live and work on the verdant slopes of the Hollywood Hills. Although he left no blood relations in this country, his friends - his true family - know his story well.

VIRTUOSO, AVANT-GARDIST, TUNESMITH, FILM COMPOSER, television personality: Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisel (1899-1988) played each of these roles gracefully during his long, productive life. Driven from his native Germany in 1933 by the gathering eddies of war, this slight, bespectacled member of the Weimar intelligentia came to live and work on the verdant slopes of the Hollywood Hills. Although he left no blood relations in this country, his friends - his true family - know his story well.

Friedrich was born in 1899 in Leipzig, the eldest son in a musical family. By the age of ten he was already acknowledged to be a first-rate novelty pianist, no small achievement in this city of prodigies. Each spring and summer he would tour the Rhineland with his father, Kaspar, a well-known impresario and violinist. There exist elderly citizens of Bonn and Cologne who still can recall their amazement at witnessing this fragile-looking youth performing Chopin with his hands rotated 180 degrees at the wrist, palms illumined by the warm light of a crystal chandelier overhead and the sound of little fingernails clicking on the keys. Although it has been said that Kaspar Kreisel exploited his wunderkind, an entry in Friedrich's journal would seem to put these claims to rest:

Friedrich was born in 1899 in Leipzig, the eldest son in a musical family. By the age of ten he was already acknowledged to be a first-rate novelty pianist, no small achievement in this city of prodigies. Each spring and summer he would tour the Rhineland with his father, Kaspar, a well-known impresario and violinist. There exist elderly citizens of Bonn and Cologne who still can recall their amazement at witnessing this fragile-looking youth performing Chopin with his hands rotated 180 degrees at the wrist, palms illumined by the warm light of a crystal chandelier overhead and the sound of little fingernails clicking on the keys. Although it has been said that Kaspar Kreisel exploited his wunderkind, an entry in Friedrich's journal would seem to put these claims to rest:

"It is a difficult and drizzily season. Today Papa came close to selling his Stradivarius! Luckily, despite my high fever, I was able to play a lucrative midnight engagement at the Ratskeller and the fiddle was saved."

"It is a difficult and drizzily season. Today Papa came close to selling his Stradivarius! Luckily, despite my high fever, I was able to play a lucrative midnight engagement at the Ratskeller and the fiddle was saved."

Thanks to a student deferment, Kreisel was able to spend the war years in the Gymnasium fur Musik. His senior composition, a song cycle for soprano and full orchestra, was "audited with interest" by the headmaster's committee. Dedicated to Kaiser Wilhelm, this juvenile effort, with its grand theme and martial rhythms, evinced a growing political awareness.

Thanks to a student deferment, Kreisel was able to spend the war years in the Gymnasium fur Musik. His senior composition, a song cycle for soprano and full orchestra, was "audited with interest" by the headmaster's committee. Dedicated to Kaiser Wilhelm, this juvenile effort, with its grand theme and martial rhythms, evinced a growing political awareness.

Encouraged by his father, Kreisel applied to the prestigious Berlin Music Conservatory and, in 1921, traveled to the capital to begin his studies in earnest. He soon became part of the vital community of artists, playwrights, and musicians that thrived in the delirious atmosphere of between-the-wars Berlin. From a letter to his brother Karl,July 1922:

Encouraged by his father, Kreisel applied to the prestigious Berlin Music Conservatory and, in 1921, traveled to the capital to begin his studies in earnest. He soon became part of the vital community of artists, playwrights, and musicians that thrived in the delirious atmosphere of between-the-wars Berlin. From a letter to his brother Karl,July 1922:

"Don't tell Papa, but I have found a position playing every night in the cabaret. Everyone there has a very cynical attitude. And, Karl, I've discovered that there are no women back in Leipzig. To see a woman, one must come to Berlin! The nights have been unseasonably cool here."

"Don't tell Papa, but I have found a position playing every night in the cabaret. Everyone there has a very cynical attitude. And, Karl, I've discovered that there are no women back in Leipzig. To see a woman, one must come to Berlin! The nights have been unseasonably cool here."

Like other young modernists, Kreisel found inspiration in the cult of the new. He attended bloody prizefights and a film-shoot where he was "teased by the actresses." At a six-day bicycle race, a double-header, he found himself standing next to Walter Gropius. In the summer months, he'd sometimes ride the elevated train to the lake beaches and gawk with disbelief at the Berliners bathing in the nude. Returning to the city on the evening zeppelin, he'd head straight for the cabaret, where he felt safe from the roving bands of street toughs and the odd rooftop sniper.

Like other young modernists, Kreisel found inspiration in the cult of the new. He attended bloody prizefights and a film-shoot where he was "teased by the actresses." At a six-day bicycle race, a double-header, he found himself standing next to Walter Gropius. In the summer months, he'd sometimes ride the elevated train to the lake beaches and gawk with disbelief at the Berliners bathing in the nude. Returning to the city on the evening zeppelin, he'd head straight for the cabaret, where he felt safe from the roving bands of street toughs and the odd rooftop sniper.

In 1923, just as inflation and social chaos were at their highest, Kreisel met Hugo Spaak, the man with whom he was to share his creative destiny. Spaak was a scion of the East Prussian Von Spaaks, a crusty old line considered right-wing even by their Junker neighbors. After being discharged from the army for chronic insubordination, Spaak arrived in Berlin clutching a portfolio of stark expressionist plays. The irrefutable power of these early works - Sin City, Billy Tibet , and the others - and his raffish good looks made him an overnight success. From Kreisels' journal, April 1923:

In 1923, just as inflation and social chaos were at their highest, Kreisel met Hugo Spaak, the man with whom he was to share his creative destiny. Spaak was a scion of the East Prussian Von Spaaks, a crusty old line considered right-wing even by their Junker neighbors. After being discharged from the army for chronic insubordination, Spaak arrived in Berlin clutching a portfolio of stark expressionist plays. The irrefutable power of these early works - Sin City, Billy Tibet , and the others - and his raffish good looks made him an overnight success. From Kreisels' journal, April 1923:

"Last night at the Cafe Madrid I met Spaak, the progressive playwright, whose 'Theater of the Damned', as he calls it, has taken Berlin by storm. He affects the uniform of the industrial worker: a filthy leather coat and a miner's helmet, complete with working headlamp. He smokes the same fat cigars as Papa, and his eyes are wild. Also present was his mad mistress, Ida Gekko, the acrobat-chanteuse. Later that evening, I noticed Spaak across the room attempting to stuff the required 4 million marks into the gumball machine. Nevertheless, he is not without charm. It looks like low cloud cover through the weekend."

"Last night at the Cafe Madrid I met Spaak, the progressive playwright, whose 'Theater of the Damned', as he calls it, has taken Berlin by storm. He affects the uniform of the industrial worker: a filthy leather coat and a miner's helmet, complete with working headlamp. He smokes the same fat cigars as Papa, and his eyes are wild. Also present was his mad mistress, Ida Gekko, the acrobat-chanteuse. Later that evening, I noticed Spaak across the room attempting to stuff the required 4 million marks into the gumball machine. Nevertheless, he is not without charm. It looks like low cloud cover through the weekend."

At any rate, Spaak took a liking to the young composer, and they agreed to collaborate on a musical play after Kreisels' imminent graduation.

At any rate, Spaak took a liking to the young composer, and they agreed to collaborate on a musical play after Kreisels' imminent graduation.

Spaak's theory of drama rested on the assumption that both the actors and the audience were already damned to oblivion by the Hell-King, Authority, whose will was enacted by his horned minions: Family, Government, Commerce, Technology, and so forth - in other words, civilization itself. While Authority can't be challenged directly, one can still resist by provoking the crowd with deliberate acts of violence: in Spaak's formulation, "tiny waves of spitework" hurled toward the spectators by the "spectacleers". These intermittent squalls were calculated to disturb the narrative flow, enrage the crowd and, ultimately, to precipitate a rejection of civilized pretense in the form of a free-for-all or full-scale riot. According to Spaak's manifesto, the angry participants would suddenly become aware of their freedom to act and, in time, gain the courage to rise up against their "real world" oppressors.

Spaak's theory of drama rested on the assumption that both the actors and the audience were already damned to oblivion by the Hell-King, Authority, whose will was enacted by his horned minions: Family, Government, Commerce, Technology, and so forth - in other words, civilization itself. While Authority can't be challenged directly, one can still resist by provoking the crowd with deliberate acts of violence: in Spaak's formulation, "tiny waves of spitework" hurled toward the spectators by the "spectacleers". These intermittent squalls were calculated to disturb the narrative flow, enrage the crowd and, ultimately, to precipitate a rejection of civilized pretense in the form of a free-for-all or full-scale riot. According to Spaak's manifesto, the angry participants would suddenly become aware of their freedom to act and, in time, gain the courage to rise up against their "real world" oppressors.

This all becomes clear in Kreisel and Spaak's first celebrated collaboration, Rogues' Cantata , produced in 1925. The story, set in the Great Florida Swamp, is pure Spaak. Three scavengers - Nicky Buckshaw, his girl, Betty O'Day, and Captain Tom Ivory - get a tip about a cache of diamonds hidden in the Everglades. Setting off in a specially constructed amphibious car, they sail around in the muck and endure a series of sordid adventures too complex to describe here. For this sour stew, Kreisel created an original idiom that drew on the rhythm of Afro-American bamboula music, with a melodic gesture toward the Levant and points east. Most astonishing, of course, were the ear-cracking "wrong note" bar ballads: "Nicky'Lament," "V-I-C-E-VICE," and the renowned "Miami Liebenslied." The latter became even more famous as the signature tune of the original Betty O'Day, Ida Gekko, whose stellar career was just beginning. Spaak's lyrics, as always, depict a brutal, greed-driven America. From "Miami Liebenslied":

This all becomes clear in Kreisel and Spaak's first celebrated collaboration, Rogues' Cantata , produced in 1925. The story, set in the Great Florida Swamp, is pure Spaak. Three scavengers - Nicky Buckshaw, his girl, Betty O'Day, and Captain Tom Ivory - get a tip about a cache of diamonds hidden in the Everglades. Setting off in a specially constructed amphibious car, they sail around in the muck and endure a series of sordid adventures too complex to describe here. For this sour stew, Kreisel created an original idiom that drew on the rhythm of Afro-American bamboula music, with a melodic gesture toward the Levant and points east. Most astonishing, of course, were the ear-cracking "wrong note" bar ballads: "Nicky'Lament," "V-I-C-E-VICE," and the renowned "Miami Liebenslied." The latter became even more famous as the signature tune of the original Betty O'Day, Ida Gekko, whose stellar career was just beginning. Spaak's lyrics, as always, depict a brutal, greed-driven America. From "Miami Liebenslied":

(Betty O'Day):

(Betty O'Day):

I was barely fifteen when you found me

I was barely fifteen when you found me

Your innocent green-eyed chorine

Your innocent green-eyed chorine

You said that you worked in the roundhouse there

You said that you worked in the roundhouse there

Where you scrubbed all the engines clean

Where you scrubbed all the engines clean

I could tell from the cut of your cheroot

I could tell from the cut of your cheroot

It was lies Mr. Bucksaw

It was lies Mr. Bucksaw

But oh those American eyes Mr. Bucksaw.

But oh those American eyes Mr. Bucksaw.

(Rogue's Chorus):

(Rogue's Chorus):

We've got to have lager and cash my friend

We've got to have lager and cash my friend

If we're looking to throw the dice

If we're looking to throw the dice

Miami's an oven in the summer, boys

Miami's an oven in the summer, boys

Tell Blondie to break out the ice, my boys

Tell Blondie to break out the ice, my boys

Tell Blondie to break out the ice

Tell Blondie to break out the ice

On opening night, the combined effect of text and score proved so fiercely ironic that, before the end of the first act, one high-strung patron collapsed as his fragile sense of reality shattered and peeled away. Having tasted first blood, the actors charged onto the apron and leered at the musicians in the pit with overt carnality. Flustered, the orchestra lowered their instruments, leaving only the sound of irregular, ruttish breathing coming from the stage. The crowd became uneasy.

On opening night, the combined effect of text and score proved so fiercely ironic that, before the end of the first act, one high-strung patron collapsed as his fragile sense of reality shattered and peeled away. Having tasted first blood, the actors charged onto the apron and leered at the musicians in the pit with overt carnality. Flustered, the orchestra lowered their instruments, leaving only the sound of irregular, ruttish breathing coming from the stage. The crowd became uneasy.

In Act II, Ida, who at that time was self-administering tincture of opium on doctor's orders, unintentionally created a classic bit of business when she wandered off her mark, kick-swiveled a chair and dropped into it with her long, perfect legs wrapped around the backrest. As she trilled the first notes of the "Liebenslied" in her schoolgirl's broken soprano, steam began to rise from the mezzanine. The crowd was boiling by the final curtain, when Spaak had the actors hurl sacks filled with machine parts and motor oil from the stage. Riot and arson followed, and Kreisel and Spaak became household words.

In Act II, Ida, who at that time was self-administering tincture of opium on doctor's orders, unintentionally created a classic bit of business when she wandered off her mark, kick-swiveled a chair and dropped into it with her long, perfect legs wrapped around the backrest. As she trilled the first notes of the "Liebenslied" in her schoolgirl's broken soprano, steam began to rise from the mezzanine. The crowd was boiling by the final curtain, when Spaak had the actors hurl sacks filled with machine parts and motor oil from the stage. Riot and arson followed, and Kreisel and Spaak became household words.

Despite the partners' great success, their relationship had deteriorated badly by 1930. As the Fascists gained power, Spaak's politics hardened into a radical anarcho-syndicalism and his work became humorless and didactic. His tantrums came more frequently. In the fall of 1931 he became obsessed with the idea of an epic worker's opera on roller skates to be performed by transit union members and their wives and children. Kreisel, appalled by the musical limitations this would impose, protested. Furthermore, having received a handsome offer of employment from Colossal Studios in Hollywood, he felt that being associated with Spaak's anti-Americanism might make immigration difficult. Their various disputes culminated in a nasty scene on Christmas night, with Spaak chasing Kreisel out of the theater onto the Kurfurstendamm, screaming, "Clear out, you noisy fraud! B-town is flush with phony Wagners, and dog-cheap, too!" After a respite in London, Kreisel booked passage on the Atlantis, bound for New York City. A year later, after the Reichstag fire, a despondent Spaak, with Ida in tow, disappeared into neutral Switzerland.

Despite the partners' great success, their relationship had deteriorated badly by 1930. As the Fascists gained power, Spaak's politics hardened into a radical anarcho-syndicalism and his work became humorless and didactic. His tantrums came more frequently. In the fall of 1931 he became obsessed with the idea of an epic worker's opera on roller skates to be performed by transit union members and their wives and children. Kreisel, appalled by the musical limitations this would impose, protested. Furthermore, having received a handsome offer of employment from Colossal Studios in Hollywood, he felt that being associated with Spaak's anti-Americanism might make immigration difficult. Their various disputes culminated in a nasty scene on Christmas night, with Spaak chasing Kreisel out of the theater onto the Kurfurstendamm, screaming, "Clear out, you noisy fraud! B-town is flush with phony Wagners, and dog-cheap, too!" After a respite in London, Kreisel booked passage on the Atlantis, bound for New York City. A year later, after the Reichstag fire, a despondent Spaak, with Ida in tow, disappeared into neutral Switzerland.

From Kreisel's letter to Karl, March 1937:

"I find that Hollywood agrees with me. There are many young actresses here. The climate is mild, never harsh and raw as it is in Germany."

From Kreisel's letter to Karl, March 1937:

"I find that Hollywood agrees with me. There are many young actresses here. The climate is mild, never harsh and raw as it is in Germany."

Searching through the hundreds of scores Kreisel penned for Colossal in the late '30's and the '40's, one can find little trace of his former dissonant modernism. He was convinced, perhaps justifiably, that an illustrative, late-romantic style was more appropriate for the Hollywood film, and to this formula he stuck like glue. There is an interesting harmonic ambivalence in Lieutenant Drummond's death scene in The Comanche but this may be due to a copyist's error. For 1947's Happy Hour, the story of an adman's tipsy afternoon odyssey through the watering holes of Madison Avenue, Kreisel boldly resurrected a fragment of "Nicky's Lament" for the bar-and-nightclub montage. Although the score was bypassed for an Oscar nomination, Kreisel was more than consoled by his first marriage to the film's glamorous ingenue, Monica Towers.

Searching through the hundreds of scores Kreisel penned for Colossal in the late '30's and the '40's, one can find little trace of his former dissonant modernism. He was convinced, perhaps justifiably, that an illustrative, late-romantic style was more appropriate for the Hollywood film, and to this formula he stuck like glue. There is an interesting harmonic ambivalence in Lieutenant Drummond's death scene in The Comanche but this may be due to a copyist's error. For 1947's Happy Hour, the story of an adman's tipsy afternoon odyssey through the watering holes of Madison Avenue, Kreisel boldly resurrected a fragment of "Nicky's Lament" for the bar-and-nightclub montage. Although the score was bypassed for an Oscar nomination, Kreisel was more than consoled by his first marriage to the film's glamorous ingenue, Monica Towers.

In 1948, a House Special Committee on Un-American Activities investigator visited the Kreisel's home in Laurel Canyon and questioned the composer for several hours about certain alleged "communist affiliations." The following year Kreisel found himself facing the House committee in Washington: From the transcript:

In 1948, a House Special Committee on Un-American Activities investigator visited the Kreisel's home in Laurel Canyon and questioned the composer for several hours about certain alleged "communist affiliations." The following year Kreisel found himself facing the House committee in Washington: From the transcript:

(Senator) Parks: "Mr. Kreezel (sic), are you now or have you ever been a Communist?"

Kreisel: "No, never."

Parks: "I see. Are you acquainted with a Mr. Hugo Spaak?"

Kreisel: "Can you repeat, please?"

Parks: "Hugo Spaak."

Kreisel: "Yes, well... it's familiar."

Parks: "While you were in Germany, did you not collaborate on a series of extremist plays..."

Kreisel: "Of course, now I remember! Spaak, that pig! I worked with many people then, but this one, Spaak, he was the worst. When I found out he was Bolshevik, boom, it was finished, over."

Parks: "Mr. Kreezel, I have on my desk a copy of the sheet music of a song published in 1926, called "Whisper, Comrade"... (laughter all around)

Although Kreisel was not officially blacklisted, Colossal said it was obliged to let him go. Monica sued for divorce, claiming emotional damage and misrepresentation. The alimony was severe. Then, in the autumn of '57, he received word that his father had been killed when his tightly-strung Stradivarius exploded during a recital in Augsburg. For the first time in his life Kreisel found himself without work, income, or a place to live. Aside from freelancing a few pictures for an independent horror outfit in Laguna (Hear My Ax Declaim, The Spine Robbers ), he spent most of the late '50's doing his old novelty keyboard routine at parties under the patronizing gaze of Hollywood hostesses. From Kreisel's journal, October 1957:

Although Kreisel was not officially blacklisted, Colossal said it was obliged to let him go. Monica sued for divorce, claiming emotional damage and misrepresentation. The alimony was severe. Then, in the autumn of '57, he received word that his father had been killed when his tightly-strung Stradivarius exploded during a recital in Augsburg. For the first time in his life Kreisel found himself without work, income, or a place to live. Aside from freelancing a few pictures for an independent horror outfit in Laguna (Hear My Ax Declaim, The Spine Robbers ), he spent most of the late '50's doing his old novelty keyboard routine at parties under the patronizing gaze of Hollywood hostesses. From Kreisel's journal, October 1957:

"When I look down at my palms I can't help remembering Papa's stern visage as he marched me through the salons of the Rhineland with one hand on my shoulder, the other gripping his priceless instrument. I wonder if the explosion had something to do with the humidity."

"When I look down at my palms I can't help remembering Papa's stern visage as he marched me through the salons of the Rhineland with one hand on my shoulder, the other gripping his priceless instrument. I wonder if the explosion had something to do with the humidity."

During these years, his thoughts often returned to Berlin and Spaak, whose fate since the war was unknown to him. Racked with guilt over his betrayal of his ex-partner at the H.U.A.C. hearings, Kreisel began a course of psychoanalysis.

During these years, his thoughts often returned to Berlin and Spaak, whose fate since the war was unknown to him. Racked with guilt over his betrayal of his ex-partner at the H.U.A.C. hearings, Kreisel began a course of psychoanalysis.

Occasionally he'd see an ad in the papers for one of Ida's Los Angeles appearances, but he could never bring himself to go. In the spring of '59 Kreisel answered his phone and was startled by a voice from the past. He recorded the conversation in his journal:

Occasionally he'd see an ad in the papers for one of Ida's Los Angeles appearances, but he could never bring himself to go. In the spring of '59 Kreisel answered his phone and was startled by a voice from the past. He recorded the conversation in his journal:

" 'How's the weather, you noisy fraud?'

'But...it can't be...'

'Yes. But from now on you must always address me as Hank, Hank Silvers. Fritz, I'm writing for television. The Bud Calloway Variety Hour. Bud's favorite role was Tom Ivory in a summer stock production of Rogues' Cantata. He thinks we're geniuses. He loves us. Ida's going to be a regular.

"But your ideals...the violence, the subversion..."

"Fritz, mein Freund, we're now inside the belly of the beast.'"

The Calloway show was, of course, an enormous hit, running through 1965, when Calloway retired. Because the show has constantly been in reruns, several generations of viewers remember Friedrich Kreisel simply as Fritz, the conductor-foil for the wisecracking Calloway. Even today, children can't resist laughing as Kreisel rises from his seat behind the podium and good-naturedly endures Calloway's clever barbs ("What a weirdbeard"). Then there's the extra giggle when Kreisel sits down accompanied by a farcical gliss from the concertmaster's violin.

The Calloway show was, of course, an enormous hit, running through 1965, when Calloway retired. Because the show has constantly been in reruns, several generations of viewers remember Friedrich Kreisel simply as Fritz, the conductor-foil for the wisecracking Calloway. Even today, children can't resist laughing as Kreisel rises from his seat behind the podium and good-naturedly endures Calloway's clever barbs ("What a weirdbeard"). Then there's the extra giggle when Kreisel sits down accompanied by a farcical gliss from the concertmaster's violin.

And so Fritz Kreisel, after having worked through a rich and varied life in art, finally became a household word in his adopted country. When Bud Calloway retired, Kreisel and Spaak followed suit. Although they sometimes talked about a new collaboration, they both seemed to understand that the spark was gone. For the past twenty years, the Sunday poker match at the Zuma Golf Club - with players Calloway, Ida (when in town), Silvers, Kreisel, and director Jack DeVon - entertained "industry" onlookers with its drollery and good spirits. On those delicious weekends, the weather was most typical of the region, plenty of sunshine.

And so Fritz Kreisel, after having worked through a rich and varied life in art, finally became a household word in his adopted country. When Bud Calloway retired, Kreisel and Spaak followed suit. Although they sometimes talked about a new collaboration, they both seemed to understand that the spark was gone. For the past twenty years, the Sunday poker match at the Zuma Golf Club - with players Calloway, Ida (when in town), Silvers, Kreisel, and director Jack DeVon - entertained "industry" onlookers with its drollery and good spirits. On those delicious weekends, the weather was most typical of the region, plenty of sunshine.

*6/20/96*

siteguide |

news |

touring |

emg |

history |

the works |

contact |

home |

VIRTUOSO, AVANT-GARDIST, TUNESMITH, FILM COMPOSER, television personality: Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisel (1899-1988) played each of these roles gracefully during his long, productive life. Driven from his native Germany in 1933 by the gathering eddies of war, this slight, bespectacled member of the Weimar intelligentia came to live and work on the verdant slopes of the Hollywood Hills. Although he left no blood relations in this country, his friends - his true family - know his story well.

VIRTUOSO, AVANT-GARDIST, TUNESMITH, FILM COMPOSER, television personality: Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisel (1899-1988) played each of these roles gracefully during his long, productive life. Driven from his native Germany in 1933 by the gathering eddies of war, this slight, bespectacled member of the Weimar intelligentia came to live and work on the verdant slopes of the Hollywood Hills. Although he left no blood relations in this country, his friends - his true family - know his story well.